Marcel Garz and Jil Sörensen

Election times are often tough times for politicians. Candidates usually have a full agenda promoting their political program, and often they are closely monitored by the media. Importantly, anecdotal evidence suggests that political scandals could be orchestrated and might more likely be picked up by media outlets right before an election. This is normally bad news for the ones being accused of a transgression, as scandal coverage usually has negative effects on vote shares.

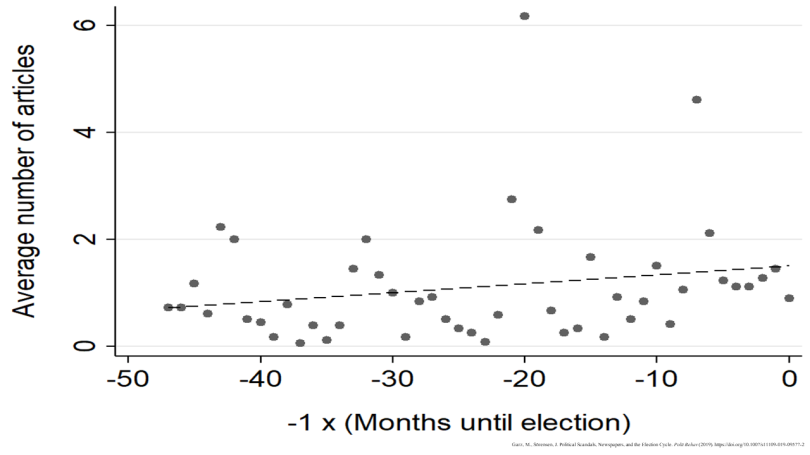

Our study examines the timing of news coverage of political scandals relative to the national election cycle in Germany. We compile an original data set of 794 newspaper articles pertaining to 71 political scandals that occurred between 2005 and 2014 in Germany. We find a positive and highly significant relationship between coverage of government scandals, but not necessarily opposition scandals, and the election cycle. On average, one additional month closer to an election increases the amount of scandal coverage by 1.3%, which accumulates to a difference of 62% between the first and the last month of a four-year election cycle. The figure below illustrates this pattern.

Scandal coverage and the election cycle

Note: The figure shows values averaged over election cycles. The dashed line represents linear predictions of the data.

In addition, we collect data on the month and year in which the transgression underlying the 71 scandals in our sample took place and calculated how much time elapsed between the occurrence of the transgression and the publication of articles reporting the scandal. Our data indicate that the length of time between transgression and publication significantly increases before an election, which could imply that certain information is “kept in the drawer” until the publication has the biggest impact.

The behavior of the actors involved in the production of scandals – political opponents, media outlets, and investigation authorities – is only partially observable to the researcher since journalists often protect their sources. Thus, we cannot determine who is responsible for the publication delay and the increase in scandal coverage before elections. However, it is possible to shed some light on the motives driving these effects. Political opponents, media outlets, and/or investigation authorities could strategically release information when it inflicts the largest damage on a candidate (i.e., presumably shortly before the election). In that case, the publication delay would be politically motivated, due to the intention to influence voters. It is also possible that media outlets postpone the publication of scandals as a way to maximize profits, because scandals might attract more attention the closer an election becomes. Thus, the publication delay could be driven by business motives, with newspapers trying to increase sales. We provide suggestive evidence that political motives likely dominate business motives in our context.